Zvonimir’s coronation was largely a result of the political scene in contemporary Europe. Namely, Pope Gregory VII (1073-1085) led an intense struggle against the German emperor Henry IV, in an attempt to subordinate the secular to ecclesiastical government, thus the election of the pope and the bishops would elude the ruler’s influence. A result of that „struggle for investiture“ was seeking allies near the Apennine peninsula, allies that would be powerful enough to resist the pressures from a mighty emperor in Central Europe. Gregory’s predecessors already made a substantial impact in these lands, not only in church matters but also politically, so it wasn’t to difficult for Gregory to find powerful people open for cooperation, in the kingdoms of Croatia, Hungary and Poland. In Croatia and Hungary, he found support in the members of ruler dynasties of Trpimirović and Arpad, two dynasties that were also bound by marriages. In Hungary, Geza was proclaimed king in 1074 with the help of his brother Ladislaus, after he banished king Solomon, who was tied to Henry IV by marriage and alliance. Already the following year, Zvonimir, who was husband to Helen, sister of Geza and Ladislaus, with their help and the help from the Pope Gregory VII’s vassal, Norman king Robert Guiscard (1057-1085) in southern Italy, dethroned Peter Krešimir IV.1 By this successful action Gregory VII on one hand enabled the new ruler an international legitimacy, and on the other hand, he got a confirmation of supremacy of ecclesiastical/papal over secular/royal government.

Zvonimir’s coronation was largely a result of the political scene in contemporary Europe. Namely, Pope Gregory VII (1073-1085) led an intense struggle against the German emperor Henry IV, in an attempt to subordinate the secular to ecclesiastical government, thus the election of the pope and the bishops would elude the ruler’s influence. A result of that „struggle for investiture“ was seeking allies near the Apennine peninsula, allies that would be powerful enough to resist the pressures from a mighty emperor in Central Europe. Gregory’s predecessors already made a substantial impact in these lands, not only in church matters but also politically, so it wasn’t to difficult for Gregory to find powerful people open for cooperation, in the kingdoms of Croatia, Hungary and Poland. In Croatia and Hungary, he found support in the members of ruler dynasties of Trpimirović and Arpad, two dynasties that were also bound by marriages. In Hungary, Geza was proclaimed king in 1074 with the help of his brother Ladislaus, after he banished king Solomon, who was tied to Henry IV by marriage and alliance. Already the following year, Zvonimir, who was husband to Helen, sister of Geza and Ladislaus, with their help and the help from the Pope Gregory VII’s vassal, Norman king Robert Guiscard (1057-1085) in southern Italy, dethroned Peter Krešimir IV.1 By this successful action Gregory VII on one hand enabled the new ruler an international legitimacy, and on the other hand, he got a confirmation of supremacy of ecclesiastical/papal over secular/royal government.

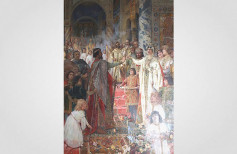

In 1075 in church of St. Peter and Moses in Solin, on St. Demetrius’ day (8th of October), Pope’s legate, abbot Gebizon, crowned Zvonimir a king of Croatia and Dalmatia.2 Zvonimir then took an oath by which he committed to serve the Pope as his vassal, whilst the Pope as his senior sent him tokens of investiture: a flag, a scepter, a sword and a crown, and promised him protection. As a vassal, the Croatian king committed to pay tax and to serve the Pope, and he also granted him the monastery of St. Gregory in Vrana. Thus, this Croatian ruler, much like Domagoj and Branimir, did not rely on the dynastic tradition, but instead on one of the most authoritative people in contemporary Europe – the Pope.3

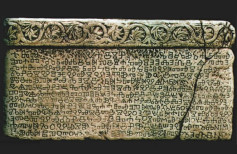

By using a double title; king of Croatia and Dalmatia, and king of Croats, or simply king of Croatia, he emphasized to certain extent the independence of Dalmatia, yet he also indicated a tighter bond of the country as a whole. He appointed a certain man named Pribimir, who’s title was „king’s vicar“, as a direct ruler over Dalmatian cities. Although historiography provided some doubts that Zvonimir ever ruled Dalmatia, the most authentic evidence of Zvonimir’s dominion over Dalmatia is „Baška tablet“ that originated around 1100 (in which Zvonimir is adressed only as Croatian king). It is a living testimony of Croatian social characteristic of Krk island and Kvarner territory. It preserved, in Croatian language and Glagolitic alphabet, a memento of Zvonimir’s grant of a lea to abbey of St. Lucy in Jurandvor near Baška on Krk island, and it also contains an inscription by an unknown stonemason representing the Croatian form of his fundamental ruler title: Zvonimir Croatian king.4 A description of Zvonimir’s seal, containing the same title in Latin, from 14th century was also preserved. It is possible that Zvonimir, in most cases, used only the title of king of Croatia, considering it to be sufficient to legitimate his authority in Dalmatia, which was then a province in which the sovereignty of the Byzantine emperor faded rapidly.

By using a double title; king of Croatia and Dalmatia, and king of Croats, or simply king of Croatia, he emphasized to certain extent the independence of Dalmatia, yet he also indicated a tighter bond of the country as a whole. He appointed a certain man named Pribimir, who’s title was „king’s vicar“, as a direct ruler over Dalmatian cities. Although historiography provided some doubts that Zvonimir ever ruled Dalmatia, the most authentic evidence of Zvonimir’s dominion over Dalmatia is „Baška tablet“ that originated around 1100 (in which Zvonimir is adressed only as Croatian king). It is a living testimony of Croatian social characteristic of Krk island and Kvarner territory. It preserved, in Croatian language and Glagolitic alphabet, a memento of Zvonimir’s grant of a lea to abbey of St. Lucy in Jurandvor near Baška on Krk island, and it also contains an inscription by an unknown stonemason representing the Croatian form of his fundamental ruler title: Zvonimir Croatian king.4 A description of Zvonimir’s seal, containing the same title in Latin, from 14th century was also preserved. It is possible that Zvonimir, in most cases, used only the title of king of Croatia, considering it to be sufficient to legitimate his authority in Dalmatia, which was then a province in which the sovereignty of the Byzantine emperor faded rapidly.

The tradition of Trpimirović branch that banished Svetoslav Suronja and their previous reputation were demolished with Zvonimir’s rise to power, which is also obvious by his renunciation of the dynasty’s family mausoleum. Two years after his enthronement, he granted the churches of St. Stephen and St. Mary, in which his most notable predecessors were buried, to the archdiocese of Split. Thus he made clear that he wanted to start a new tradition in the dynasty, relying on the Church and its head representative in his kingdom, Split archbishop Lovro.5 The most notable work from Zvonimir’s time was the construction and sanctification of Bishops church in Knin. Bishop’s court was slightly uphill, just outside the city, in a place which is even today called Biskupija (eng. Diocese).6

The tradition of Trpimirović branch that banished Svetoslav Suronja and their previous reputation were demolished with Zvonimir’s rise to power, which is also obvious by his renunciation of the dynasty’s family mausoleum. Two years after his enthronement, he granted the churches of St. Stephen and St. Mary, in which his most notable predecessors were buried, to the archdiocese of Split. Thus he made clear that he wanted to start a new tradition in the dynasty, relying on the Church and its head representative in his kingdom, Split archbishop Lovro.5 The most notable work from Zvonimir’s time was the construction and sanctification of Bishops church in Knin. Bishop’s court was slightly uphill, just outside the city, in a place which is even today called Biskupija (eng. Diocese).6

Papal protection was more than effective – in 1079 pope Gregory VII sent a letter to knight Vecelin, brother of late Istrian margrave Ulrich I Weimar Orlamünde, threating to excommunicate him from the Church, if he does not stop the attacks on Kingdom of Dalmatia. However, when the dark days have come for pope Gregory VII, in his conflict with the German king, who defeated all of Pope’s allies in Germany, and then came to Rome to take revenge on the Pope, Croatian king Demetrius Zvonimir and the brother of then late Hungarian king Geza, new king Ladislaus (1077-1095) remained faithful to the Pope.7

Papal protection was more than effective – in 1079 pope Gregory VII sent a letter to knight Vecelin, brother of late Istrian margrave Ulrich I Weimar Orlamünde, threating to excommunicate him from the Church, if he does not stop the attacks on Kingdom of Dalmatia. However, when the dark days have come for pope Gregory VII, in his conflict with the German king, who defeated all of Pope’s allies in Germany, and then came to Rome to take revenge on the Pope, Croatian king Demetrius Zvonimir and the brother of then late Hungarian king Geza, new king Ladislaus (1077-1095) remained faithful to the Pope.7

Other articles from the series: “The Trpimirović Dynasty of Croatian Rulers”

- From the Arrival and Settling of Croats to Trpimir Ascending to the Throne

- The age of duke Trpimir

- Dukes Domagoj and Zdeslav

- Branimir and Muncimir

- The age of kings – Tomislav

- Church Councils and King Tomislav’s Heirs

- Stjepan Držislav

- The Heirs of Stjepan Držislav

- Petar Krešimir IV

- Demetrius Zvonimir

- Demetrius Zvonimir and Stephen II

- Although Zvonimir profited from the kindred relationship with the Arpads, it will prove later that they gained much more from him then he did from them. On the grounds of Zvonimir’s marriage with Helen, they claimed the Croatian throne, and subsequently took it over.

- Neven BUDAK, Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb: Hrvatska sveučilišna naklada, 1994

- Branko FUČIĆ, Hrvatski glagoljski i ćirilski natpisi, Supičić (ed.), Srednji vijek (VII. – XII. stoljeće)…, p. 259-283

- Ivo GOLDSTEIN (ed.), Zvonimir, kralj hrvatski, Zbornik radova znanstvenog skupa “Zvonimir, kralj hrvatski”, Zagreb: HAZU – Zavod za hrvatsku povijest Filozofskog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu, 1997

- Stjepan GUNJAČA, Ispravci i dopune, knjiga II., Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1973 – 1975

- Vjekoslav KLAIĆ, Povijest Hrvata, vol. 1, Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, 1972.

- Lujo MARGETIĆ, Hrvatska država u doba narodnih vladara, u: Ivan SUPIČIĆ (ed.), Srednji vijek (VII. – XII. stoljeće): Rano doba hrvatske kulture, vol. I, u: isti (ed.) Hrvatska i Europa: kultura, znanost i umjetnost, Zagreb: Hrvatska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, 1997

- Tomislav RAUKAR, Hrvatsko srednjovjekovlje, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1997

- Tomislav RAUKAR, Prostor i društvo, u: Supičić (ed.), Srednji vijek (VII. – XII. stoljeće)…, p. 181-196

- Jakov STIPIŠIĆ, Pitanje godine krunidbe kralja Zvonimira, u: Goldstein (ur.), Zvonimir, kralj hrvatski…, p. 57-66

- Ivan SUPIČIĆ (ed.), Srednji vijek (VII. – XII. stoljeće): Rano doba hrvatske kulture, sv. I, u: isti (ed.) Hrvatska i Europa: kultura, znanost i umjetnost, Zagreb: Hrvatska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, 1997

- Franjo ŠANJEK, Crkva i kršćanstvo, u: Supičić (ed.), Srednji vijek (VII. – XII. stoljeće)…, p. 217-236

- 1 Stjepan GUNJAČA, Ispravci i dopune starijoj hrvatskoj historiji, vol. II, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1973, p. 141-167

- 2 Jakov STIPIŠIĆ, Pitanje godine krunidbe kralja Zvonimira, in: Ivo GOLDSTEIN (ed.), Zvonimir, kralj hrvatski, Zbornik radova znanstvenog skupa “Zvonimir, kralj hrvatski”, Zagreb: HAZU – Zavod za hrvatsku povijest Filozofskog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu, 1997, p. 57-66; Franjo ŠANJEK, Crkva i kršćanstvo, Ivan SUPIČIĆ (ed.), Srednji vijek (VII – XII. stoljeće) ): Rano doba hrvatske kulture, vol. I, same (ed.) Hrvatska i Europa: kultura, znanost i umjetnost, Zagreb: Hrvatska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, 1997, p. 231-232

- 3 Neven BUDAK, Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb: Hrvatska sveučilišna naklada, 1994, p. 46; Franjo ŠANJEK, Zvonimirova “zavjernica” u svjetlu crkveno-političkih odrednica grgurovske reforme, GOLDSTEIN (ed.), Zvonimir, kralj hrvatski, Zbornik radova znanstvenog skupa “Zvonimir, kralj hrvatski”, Zagreb: HAZU – Zavod za hrvatsku povijest Filozofskog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu, 1997, p. 27-35; Tomislav RAUKAR, Prostor i društvo, in: SUPIČIĆ (ed.), Srednji vijek (VII. – XII. stoljeće)…, p. 183-184

- 4 Branko FUČIĆ, Hrvatski glagoljski i ćirilski natpisi, SUPIČIĆ (ed.), Srednji vijek (VII. – XII. stoljeće)…, p. 266-268; RAUKAR, Hrvatsko srednjovjekovlje, Zagreb: Školska knjiga, 1997, p. 50; Lujo MARGETIĆ, Hrvatska i Crkva u srednjem vijeku: Pravnopovijesne i povijesne studije, Rijeka: Pravni fakultet Sveučilišta u Rijeci, 2000, p. 351-386

- 5 BUDAK, Prva stoljeća Hrvatske…, p. 47

- 6 Vjekoslav KLAIĆ, Povijest Hrvata, vol. 1, Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, 1972, p. 142

- 7 Same, p. 140-141

Your comment